The final part of the story of the Metropolitan Police’s trial use of the infant, monochrome closed circuit television in the 1960s, from a file at the National Archives at Kew in west London. One test was at Hatton Garden, then as now a centre of the London and indeed European jewels trade, and thus a magnet for thieves besides reputable dealers. The building the police chose to site their operation would become infamous 60 years later.

Hatton Garden had run for four weeks, from Monday, July 12 to August 9, 1965; two cameras were fixed to number 88 to 90, selected because it held a large safe deposit business. In 2015 it suffered an elaborate robbery, over the long Easter weekend, which has spawned books and films. In 1965, police noted ‘members of the jewellery trade deposit large quantities of valuable diamonds and precious stones between 4pm and 530pm and collect them again from 9am when they visit various buildings in Hatton Garden and Greville Street to show and sell their goods’. The man doing the monitoring was in a store on the roof, and could pan about 120 degrees, to cover the (straight) street.

As a clue to how CCTV was, to state the obvious, a sort of television, the camera’s 10:1 zoom was described as ‘the same technique as used on commercial television for example when a footballer is selected by the cameraman and seemingly brought forward towards the viewer until he occupies most of the screen, all other objects surrounding him or nearby disappearing whilst this zooming action is taking place’. TV’s zoom was still novel enough to need explaining. So was iris control; to adjust for more or less light, or shade. The camera also had a heater, and wiper. Each plain clothes patroller had a walkie-talkie in their pocket. Police had worked out how to pass word from the man monitoring the camera to the street, discreetly enough so that the criminals did not take fright. Instead of the radio’s normal rigid aerial, ‘a flexible wire was fed down inside the sleeve of the jacket worn by the operator’ and a microphone also on a lead was fed down the jacket sleeve, into the hand, Det Insp A Thomson reported. Police worked out radio etiquette; they named 88-90 Hatton Garden as ‘Diamond Control’ and the patrollers as ‘Diamond One and Two’. A ‘Diamond Three’ walkie talkie was at nearby Grays Inn Road police station. A Det Sgt Hall was in charge; ‘this officer has made a hobby and study of radio and television’.

Their first arrest came in their second week, on July 21. The camera picked out a youth loitering and the 18-year-old admitted he had escaped from a training school in Newcastle. On Friday, July 23, police made a second arrest, again a loiterer, who admitted stealing cash from a news vendor’s stall. On July 27, a man got out of a car under observation, and turned out to be wanted by police at Exeter. As for the actual crime the experiment was there to tackle, the kerbside dealers of stolen goods after a week ‘obviously moved the venue of their trading’, ‘but the biggest factor of all was the impact made upon the legitimate business traders in the area. It is a well known fact they were delighted about the extra protection afforded to them.’ Higher-ups at the Met described Thomson’s report as interesting and valuable; but the results at Hatton Garden had been ‘not exceptional’. The seven officers under Hall, who had built up knowledge about the ‘doubtful traders’ returned to their different stations.

Here lay profound questions for policing. An occasional operation here and there might please locals, but did it merely give a respite from crime? Did police make the most of the local insights they gained? And as it took humans to apply that knowledge, was CCTV, or any mechanical invention, a necessary ingredient? Police noted that after they removed the cameras, rumours spread that hidden cameras were in operation; ‘needless to say these will not be dispelled’. That did raise the question of whether police were being honest.

Cities were taking up CCTV, for traffic control; Toronto had detector loops passing information about traffic to a computer in city hall, that was controlling traffic lights. But a camera could look no further, and not in any better definition, than what a man could see with binoculars. CCTV (a term seldom used; people still spelt out ‘closed-circuit television’) might have a use in maintaining security of property; but that was for the building owners, rather than police.

Strikingly, police, far from put off, kept coming up with ideas. Chief Supt JA Rennie at Bramshill staff college suggested adding CCTV to the mobile police station. Someone else doubted that the vehicle’s generator could operate the television equipment too; ‘however with an incident such as a rail or aircraft accident the greatest value of such an overall picture would be in the first hour or two when rescue work would be at its height; yet there is likely to be a delay or two to three hours before the mobile station could reach the site’. In any case the weather might be bad or dark, and television might then be ‘useless’.

Still, in a long report of November 1964, Rennie suggested taking up CCTV, for its non-police uses. He gave the example of the 600 acre park at Stoneleigh, that used CCTV for traffic and policing or shows. Rennie proposed permanent installs of cameras for ‘big occasions’ such as the FA Cup final, and Derby Day. He singled out Strand Underpass, where a patrol in the morning had to check for any broken-down cars; and sports grounds such as Arsenal and Tottenham, and White City; and against CND demonstrations in Trafalgar Square. “For security purposes CCTV has an immediate appeal,” Rennie went on. For instance, some businesses had their safe ‘in rather obscure places’, that CCTV could well offset, with a screen in view of the passing patrolling policeman. “If we could push this idea to firms, it might well substantially reduce safe blowing crimes.” Royal residences – Rennie named Windsor Castle, Buckingham Palace and Kensington Palace ‘might well lend themselves to the installation of CCTV to improve security; as in other fields the possibilities are endless’. So they were; except that the actual machines could not match the police’s wishes.

A clue to what lay behind these common urges by senior police to apply machinery came in a meeting on CCTV on Thursday afternoon, January 12, 1961; between several men of commander and superintendent rank and above. Each man considered cameras in terms of his department’s work. Det Supt SC Cudmore of C5 branch (CID policy and secretariat) mentioned Derby Day pick-pockets. Even if police saw a pick-pocket, the crowds were too dense to do anything. As for thefts from cars in large West End squares; a policeman with binoculars could do the same. Still, Cudmore favoured use of new equipment, ‘because thieves were availing themselves of technical aids where possible and police could not afford to lag behind …. in spite of this he could not put forward any really good reasons for introducing the equipment at present’. Det Supt LV Gale of Special Branch likewise had considered CCTV; for identifying speakers at open air meetings; scanning areas on ceremonial occasions for trouble-makers, to save manpower; and for viewing crowds on a route when so thick that Special Branch could not pass a message (by hand) back to base. At the meeting, ‘everyone was in agreement that closed-circuit television ought to have an application in various aspects of police work but that these were difficult to define in its [CCTV’s] present state of development’.

From the start, senior police laid down that any use of cameras – or rather, spending on them – must be offset by a saving in manpower. For years, the Met could not justify CCTV on those terms. Why then did they keep trying? Partly, because the CCTV alone was not at issue; to work, police knew from the start that the officer at the monitoring screen had to communicate with the officer at the scene. CCTV, then, was part of a larger development of means.

CCTV also brought good, or at least unquestioning, publicity. That first use for the Thai royal visit made headlines in most national newspapers. The Daily Telegraph for example: ‘TV watch on crowds at state visit’. CCTV was part of a far greater taking up of machines in everyday life beyond policing, including television.

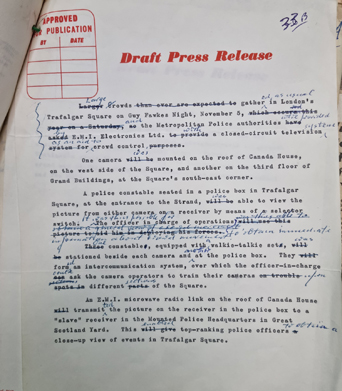

Photo courtesy of the National Archives, from file Mepo 2/9956. While police trials with CCTV in public drew nothing like the querying on privacy grounds that it would today – in an era far less deferential to authority – the authorities did accept the need for publicity, or at least to feed the print media with news, duly lapped up. Here is a draft press release by the electronics firm EMI to explain their trial pair of cameras in Trafalgar Square in July 1960 – so public, the police could hardly have kept them secret even had they wanted to.

About Met Police history

The Met Police heritage centre on Lillie Road, beside Earls Court, is shut. The Met does however collect items of historical interest such as uniforms, photographs, documents, equipment and books. Visit https://www.met.police.uk/museums.