Occasions did not come more high-profile than the investiture of Prince Charles as the Prince of Wales in the summer of 1969. Nor were the risks more stark to the heir to the throne.

The security of the prince had to be assured. And yet the investiture went again the usual rules of guarding a royal; the date, and place, of the occasion were in public, well in advance, giving anything with evil intent ample chance to make an effort to disrupt the ceremony, and embarrass the country, or worse. A file at the National Archives at Kew opens in November 1967, with Caernarvon CID taking the Welsh nationalist threat to stop the investiture ‘very seriously’. The police proposed that Caernarvon Castle employ a watchman with an Alsatian dog to patrol inside.

In April 1968, the chief constable for Gwynedd (North Wales) passed on a detective sergeant crime prevention officer’s survey of Caernarvon Castle, to the Ministry of Works at Cardiff – the central government department in charge of such monuments. The survey began by admitting complete security of the castle, especially in darkness, was ‘a Herculean task’. It was obvious that in the dark it was easy to approach the castle and place explosives against the walls. Police recommended floodlighting. It as also easy to plant an explosive charge, as a sight-seer in the day, in a suitcase, or parcel, and then leave the castle normally. After the gate closed for the day, it was imperative to search for anyone on the premises, and if any objects had been left behind.

The survey noted several small slits within ten feet of the ground level. Even if the walls (ever since Edward I built them to impose English rule on the region) were thick, an explosion would have ‘symbolic value’. Besides, it would be easy to access the castle when closed, via Eleanor’s Gate.

Making site security yet trickier was the reality that, as the sergeant acknowledged, Caernarvon Castle was one of the country’s biggest visitor attractions, ‘and that anything that might detract from its aesthetic value is to be abhorred’.

In May 1968, Geraint Walters of the Ministry of Works in Cardiff wrote to the Permanent Under-Secretary of State at the Welsh Office, GH Daniel. While they could not overlook the police recommendations, the lighting and overtime for daily searching would cost ‘a substantial amount of money’. In reply, Daniel as a good civil servant also stressed the need to avoid any unnecessary spending, and suggested the Army could help, by loaning searchlights.

The authorities were also at work, well in advance, on security passes; and vetting (by local police) of Ministry of Works employees and contractors. Vetting would consist of tracing next of kin and checking past work, without those checked knowing. The contractors, to put up scaffolding inside the castle for the seating for the occasion, were coming from Coventry. Local police were asking in November 1968 whether police or the Ministry of Works would check the passes; because a tendering company might need to enter the castle, to prepare a quotation. Besides temporary seats, the castle would need temporary toilets.

Police were also in contact with the (named in the file) director for Wales at ‘Box 500’, a coded way of saying MI5, the Security Service. Even several months before the big day, the clock was ticking; the castle would be closed to the public from February 1, 1969. A Ministry of Works memo in November 1968 noted that officials, and ‘radio and TV etc’ would need access, without applying for a pass with security clearance; they would need a temporary pass, signed for and given back when the visitors left, and retained by the castle.

Next; how to do passes; click here.

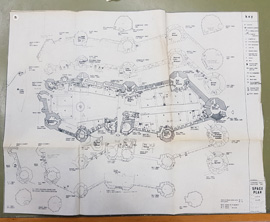

Image; plan of Caernarvon Castle, file WORK 21/147, National Archives.