Author: George Styles

ISBN No: 0 86002 133 5

Review date: 19/04/2024

No of pages: 187

Publisher: William Luscombe

Publisher URL:

n/a

Year of publication: 19/05/2017

Brief:

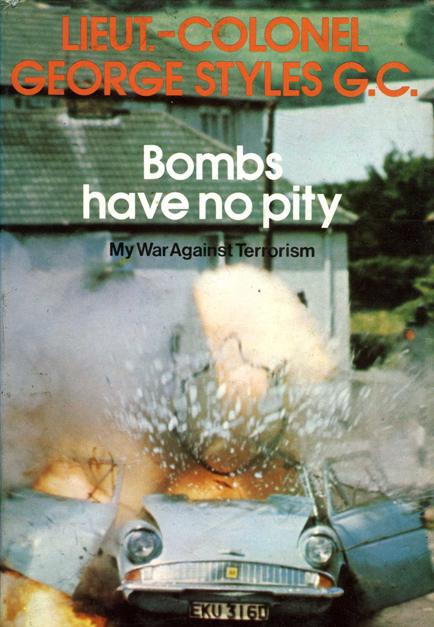

Bombs have no pity: My war against terrorism, by Lieut Colonel George Styles GC, as told to Bob Perrin. Hardback, published 1975

Bombs have no pity: My war against terrorism, by Lieut Colonel George Styles GC, as told to Bob Perrin.

As his George Cross citation put it in 1972, Styles was responsible for the supervision of the Explosives Ordnance Disposal teams in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps deployed to deal with the ever-increasing number of explosive devices used in the terrorist campaign’ in Northern Ireland. Or as the then Prime Minister Ted Heath was told when Styles met him, Styles was a ‘bomb man’, based in Belfast during the first years of the ‘Troubles’, or what Styles in his memoir published in 1975 admitted was a civil war.

Styles was given the GC for his work making safe a bomb set in the Europa Hotel in Belfast in October 1971; then, two days later, he was called to the same place to dismantle an ever larger device. Styles’ book is important – not only as a fascinating and exciting first-person read – for giving a new perspective on the Northern Ireland campaign. While we may look back on it from the 21st century and compare it to current Islamic fundamentalist terrorism – why for example are the terrorists in western European countries turning to vehicles and knives as their weapons, not bombs, as in the Madrid rail and 7-7 attacks of the mid-2000s – in truth those serving in Northern Ireland had a background in previous decades and conflicts; Styles for example was a veteran of the long 1950s campaign against Communist insurgents in Malaya, and retired from the Army in 1974.

As Styles sets out towards the end of his book, by the 1970s the British were listened to as the experienced voice on countering terrorism, because of the sheer number of explosions in Northern Ireland – 5,000 in the three years since 1969. For example on July 21, 1972 terrorists exploded 22 bombs in the city centre, killing nine and injuring 130: “Pictures on television that night showed the awful scenes as military policemen used shovels to pick up the remnants of dead soldiers and put them in plastic bags.” By 1973, the IRA campaign came to London: outside the Old Bailey, at Harrods and other department stores; mainline stations; the Tower of London; letter bombs that took the receiver’s hand off. Styles points out a lack of co-ordination between Army and the police – in other words, the time while the bombs were only exploding in Northern Ireland had not been put to any good use to prepare on the mainland – and inertia of ‘near sighted civil servants’ and among the politicians they served.

Styles’ book is a grim reminder – it ends with the Birmingham pub bombings of November 1974 – of just how bad the era was in terms of terrorist violence, and we should beware of falling into the trap of the ‘good old days’ of the IRA that rang in coded warnings (except when they were inefficient and the bombs went off before evacuation, as at Birmingham, or even blew up the men laying the bombs) compared with the suicide attackers of today.

Also a useful reminder is Styles’ point that the main enemy in the terrorist ranks in those times, ‘despite what was thought in the early days of Northern Ireland, he’s not the gunman but the bomber’. The gunman was no more than a nuisance, a settler of scores and a murderer, while ‘it’s the bomber who is the main target for any society fighting the terrorist’. Styles made the shrewd point that the man planting the bomb was actually at the low end of the pyramid of command (although doing a dangerous job, liable to get himself killed), as the bomb designer with the technical knowledge was the man at the top. As shrewdly, Styles saw that society had to strangle the terrorists’ supply of detonators – such practical methods making it harder for the terrorist to operate.

On page 178, towards the end of his book, Styles set out, ‘in the middle of a terrorist war’, what the public and industry had to expect and do. Much of it sounds sensible and indeed the security management norm in the 21st century; bag searches, parking restrictions, a ‘clear desk’ policy in workplaces so that ‘an alien package’ can be spotted quickly.

It’s striking too how in this era so much of the procedures and products that are taken for granted by security practitioners were being worked out, such as the ‘sniffer’ device to detect signs of people who had recently handled explosives; places such as the Europa Hotel cutting the number of entrances, ideally to just the one, to better control access; and the ‘mechanical tortoise’ with remote TV cameras to drive up to a suspect device.

Styles’ book, as it was published in 1975, gives us an account of the times without the benefit for good or bad of perspective. At one point (page 149) Styles argued that the ‘troubles in Northern Ireland were not local symptoms of social unrest. It was warfare, though of another kind for modern Europe. Sometimes I wondered if this was the start of World War III … urban guerrilla warfare’. Perhaps the IRA of the 1970s and the jihadists of the 21st century do have something in common.

Above all, Styles’ story reminds us of how bombs killed, including his RAOC EOD colleagues, who walked a narrow tightrope every time they were called to a suspected bomb. “You can train a man to the nth degree, you can give him courage and skill and caution, but you can’t give him good luck.”