Here Mark Rowe continues his occasional series on security topics in history, with the story of one of the more interesting Englishmen of the 20th century, Wing Commander EJ Hodsoll.

Hodsoll, born in 1894, son of a Royal Navy commander, was an apprentice at the Great Western Railways (GWR) works in Swindon from 1911 to 1914. By the mid-1930s he was tasked by the Home Office to set up Air Raid Precautions in case of war with Germany, from scratch. ARP, later known as civil defence (CD) went from a handful of staff and next to no money to the fourth arm of defence. During the 1939-45 it was one of Britain’s largest ever voluntary organisations, with hundreds of thousands of trained, uniformed and equipped staff, mainly volunteers (think of the Bill Pertwee character in BBC TV’s Dad’s Army).

Just as anything to do with terrorism in this century is newsworthy, in the late 1930s anything to do with ARP was. Counter-terrorism and security people will recognise the tightrope that Hodsoll had to walk, between being true to himself and doing the job as best he could – seeking more budget, publicising the threats and what people ought to be informed about – while not falling foul of his employers. Among his papers that are kept at Churchill College, Cambridge is a 1938 letter from the then Home Secretary Samuel Hoare, that with impeccable politeness threatens Hodsoll if he carries on making public statements that may give Hoare’s political opponents ammunition, scare the public and make Hoare look asleep on the job.

In the Second World War Hodsoll’s job as inspector-general took him around the country; later in the war he went to North Africa and Antwerp, to arrange civil defence against German aircraft bombing and V-weapons respectively. As Britain started civil defence anew around 1950 in case of a nuclear Third World War, Hodsoll returned to the field and lived in Paris working on CD for NATO. He retired to Milford on Sea and died in 1971. An important enough man for the Imperial War Museum to hold a portrait of him.

As Hodsoll wrote to the military historian Basil Liddell Hart in 1964 (a letter now kept at the Liddell Hart Centre, Kings College London): “When I left the Committee of Imperial Defence I was practically dragged out of the RAF to go and start Civil Defence in this country. I didn’t want to leave the service at all but as I was about the only person who knew anything about the subject I felt it was my duty to take on the job which as I suspected at the time became a life sentence. It was intensely interesting to have the job of creating something quite new and of a kind which had never before had to be done in this country. It was very frustrating at times especially the apathy of the early days; I started in 1935 and the Home Office nearly drove me round the bend at times as they would try and treat civil defence as just another piece of civil service administration instead of one of the biggest human problems the country has ever faced. However I think we managed to put up a good show despite it all.”

In those 70 years from his birth, the threat from the air rose unimaginably; it went from whatever could be dropped from a hot air balloon to megaton nuclear bombs that could flatten a city for miles.

At Churchill College is a typed paper dated January 1966, ‘Reflections on civil defence and survival’, by Hodsoll; still of relevance today, as he had in mind not only nuclear, but also chemical and biological, ‘or some weapon at present unknown’. He wrote: ‘… all experience goes to show that the majority unless there is a real crisis do not take much interest, and furthermore most governments are not prepared for political reasons to press them very hard. And if the population is expected to put its hand into its own pocket to help in its defence the result is a foregone conclusion.’

How much warning might we have of an attack? A bolt from the blue was unlikely, but the difficulty may lie in reading signs, he suggested. And understandably democratic governments were reluctant to act in case it was provocative in a time of tension. How long would it take to mobilise and equip civil defence and evacuate people from large cities (the assumed policy in a nuclear war in the 1950s, though quietly dropped over the 1960s)? How long would the public take to stock up emergency supplies?

Then came ‘the survival problem’ after heavy casualties. While the political threat of nuclear war was receding even as Hodsoll was writing, his comments at the end are if anything even more applicable today, on the need for the public to be self-reliant. In an emergency, the public would have to take a share of responsibility of things normally done by government. ‘Unfortunately the whole tendency today is in the opposite direction … the youth of the country must be taught self-reliance and initiative.’ Hodsoll suggested Scouts and Guides and in schools.

‘Unfortunately in some countries especially Britain there is a great prejudice against embodying anything even remotely connected with war in school curricula on the wholly erroneous grounds that it will engender a warlike spirit in children as if it was not already there from birth and will be bad for them on moral grounds.’ He likened such instruction to fire insurance for your home. Self-help should include first aid and home nursing, and elementary fire fighting.

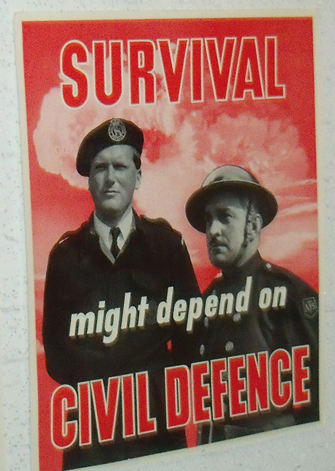

Image: UK Government recruiting policy, 1950s-1960s, for civil defence volunteers.