Leaked documents matter – as the Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning cases, and the Pentagon and Panama Papers in the 1970s and 2010s respectively show. Yet a 1976 case from the centre of British government shows how hard it was to prevent a security breach.

Prime Minister James Callaghan in November 1976 described the findings of an examination of cabinet document security, by Privy councillors no less, as ‘satisfactory’. The report had not come up with ‘any radical proposals’, but rather recommended ‘some tightening up of existing practices’. While Callaghan continued to stress how important the confidentiality of Cabinet documents was, and ‘the doctrine of collective responsibility’, the PM was careful to strike a moderate note – disagreeing with a separate study that had suggested ‘criminal sanctions’ for those who leaked. Callaghan also pointed to the competing principles of complex, modern government – the ‘need to know’ principle so that Cabinet ministers could debate policies without feeling they had to hold back for what others might think, and what Callaghan termed ‘the requirements of efficient administration’, in other words the need to know what’s going on.

The Privy councillors led by a past minister, Lord Houghton of Sowerby, were tasked by Callaghan with investigating ‘the procedures for handling Cabinet and Cabinet committee papers inside the Government’, papers and memos circulated to Cabinet ministers, and minutes of their discussions; to see if procedures were protecting confidentiality. That covered the physical security and storage of documents. Meanwhile the police were looking into a specific case; leaking of documents about child benefit – namely, how Labour in power had gone back on a commitment to bring in such a benefit.

This story is from a Cabinet document, Cab12-192-32, that is free to download from the National Archives. As background, documents about child benefit that showed an embarrassing Labour u-turn were leaked by one future Labour minister to another – by Malcolm Wicks, then a civil servant, to Frank Field, then director of the Child Poverty Action Group. Frank Field wrote about the affair on his website in 2014. As a sign of how one leak informed another, Field called Wicks ‘Deep Throat’ – harking back to the source of the Watergate revelations in the United States – to protect the leaker’s identity. Field was suspecting that his phone was tapped as police investigated the source of the leak (‘I would have authorised the tapping of my phone’, if Home Secretary, Field acknowledged in 2014). Field caused the leak by anonymously writing an article for New Society magazine.

As another sign of how Britain in the 1970s was paper-based – and what the stakes were in such high politics – as Frank Field recalled, he burned all the papers after he wrote the article, and burned the relevant parts of his diary.

As Lord Houghton’s report acknowledged, ‘high standards of security is helped if the movement of papers is restricted as far as possible’. Yet at the same time, over the decades government had grown considerably, and officials had to handle Cabinet documents – in other words, there was ever more potential for leaking. The handling of such sensitive papers of national interest rested on ‘trust’, Houghton pointed out – senior officials being allowed some discretion to get things done in good time. In sum, as the report said, there had to be a balance, between security and ‘operational needs’.

The investigators heard from several government departments and as their report put it carefully, standards of control of documents were ‘varying’. Some departments had, in that wonderful phrase, ‘room for improvement’. As the report hinted, rules to secure documents might fall by the wayside if things were to get done and if those who had to see documents were to see documents in good time – especially if government departments were physically based outside London.

Interestingly, the investigators noted that a ‘lead from the top’ was important; in other words, if those at the top set an example and kept to the rules, whether officials or ministers, others below them in hierarchies would follow that example, and vice versa. Significantly, the report went on to point out the temptations – ‘to drop a word to a backbencher here or a journalist there’. As the report hinted, junior ministers and special advisers to ministers might feel that they had a ‘need to know’.

The report reaffirmed the ‘right to know’, ‘that no one other than a member of the Cabinet or one of its Committees has any right to know unless this is essential to the proper discharge of his duties’. What went on in the Cabinet room, to put it another way, written and spoken, was classified. However that ‘need to know’ was as the report admitted, a judgement and not a set of routines.

The report shows the UK Government of the 1970s worked in a paper-first world, quite unlike the digital 21st century. The Cabinet Office, then as now, was the government department about government. It had a typing pool – typists that typed documents – and was in charge of the list of what documents got circulated to whom. As the report noted, circulation lists always tended to grow and needed ‘periodical pruning’. The investigators found different ways of record-keeping of who got what documents.

Speaking practically, the report suggested that each department should have a ‘Cabinet documents officer’, to be the point of contact with the Cabinet Office. For decades it had been laid down that Cabinet memos should be taken from one office to another ‘in distinctive folders’. While you might think that drew attention to something, the investigators commended that, for pointing out the need for ‘careful handling’. While each copy of a document was numbered, the investigators found that record systems were not ‘always comprehensive’. In other words, you might not know what was passed to whom.

The report introduced another idea, of ‘the need to retain’, and urged that documents ‘should not be retained a moment longer than is necessary’. The same applies to any information, even digitally held, today; that data has a lifecycle and can be compromised at any stage, even when deleted (whether left in a filing cabinet and forgotten about when sold second hand, or on a physical server).

Simply having rules, the report summed up, was ‘only part of the story’; people had to be reminded of them.

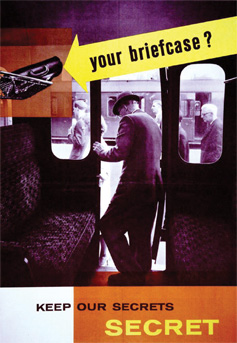

Image courtesy of the National Archives; from file INF 13/203, a 1960s-era poster warning civil servants against leaving their briefcase on a commuter train.