After the shock of the suicide bombs of 7-7, some contrasted such jihadism with the IRA bomb campaigns from the 1970s to 1990s. Whereas Islamist terrorists sought only to kill – and were not interested in living after their deed – Irish republican terrorists were selective in their targets; and rang giving warnings to allow evacuation of a scene. Such comparisons soon passed – the generation that had to face the IRA gradually went into retirement and jihadist atrocities became ever more grotesque, crowding out memories of attacks of past decades. But the comparisons hardly give justice to how deadly and nasty the IRA were – and still are; according to the Security Service MI5, the official threat level for Northern Ireland-related terrorism in Northern Ireland is severe; and on mainland UK, substantial.

List

As for the IRA being somehow more civilised than jihadis, what about the briefest list of their bombings: in Birmingham pubs (1974), outside Harrods department store in London (1983), the Grand Hotel at Brighton during the Conservative Party conference (1984), the blowing up of Tory politicians Airey Neave (House of Commons car park, 1979) and Ian Gow (home, 1990) and Lord Mountbatten (boat, Sligo, 1979). Arguably even more horrifying are the might-have-beens. A sad truth about security – against terror and home burglary alike, and in retail loss prevention – is of displacement; if two shops sell beer and one puts it behind the counter in a locked cabinet and the other piles it at the front door, the shop that makes theft harder may not sell so much, as buying is less convenient for the genuine shopper; but the thief will go where it’s easier. If high-profile sites have more security, terrorists go for easier, ‘softer’, targets. In his charming memoir, It’s All Going Terribly Wrong, Michael Parker, who in his Army service produced military tattoos and the Royal Tournament at Earls Court in west London, recalled security was ‘always a major concern’. A bomb that went off at the Tower of London (in 1974 killing one and injuring mainly tourists) ‘had actually been brought to Earls Court but could not be got through our cordon’. For the tournament, all the acts in the show had their own pub to go to, ‘in the vain hope of avoiding inter-service punch-ups’. Organisers had sought a drinks licence to open their own bars, but local government said no. A knapsack containing explosive was found in one of those pubs. Its firing mechanism was faulty, which saved lives: after that, Parker had no difficulty getting licences.

Bomber the enemy

A still more relevant memoir, dating from 1975, the early days of the Irish ‘Troubles’, was Bombs Have No Pity, by a newly-retired Army bomb disposal man Lieut Colonel George Styles. He wrote of some of the 5000 explosions in Northern Ireland in the three years from 1969: ‘it’s the bomber who is the main target for any society fighting the terrorist’. A detonator, that in those days cost five pence (lawfully bought), could do £50,000 of damage; which bears comparison with the 9-11 attack that for the cost of flying lessons and one-way airline tickets and box-cutter knives, killed thousands and brought down two New York landmarks. Styles argued for tighter control over these materials. He set out how, ‘in the middle of a terrorist war’, the public for their own safety had to accept some erosion of personal liberty. And so it has turned out: bag and body searches, parking restrictions. His advice to industry sounds strikingly up to date. “Management should ensure that the ‘clear desk’ philosophy is carried out by workers on the factory floor,” so that an ‘alien package’, perhaps a bomb, would be spotted quickly. The company post room should be on the outside of a building and have plenty of windows: “Thus the blast of a letter bomb or a bomb in a parcel will be directed outwards through the glass and not inwards.” The ‘vital innards’ of a firm – its electrics in Styles’ time – should be well inside the building, well away from bombers who might walk in off the street. Styles pointed to the need for Army bomb disposal and the police to work together, and of shortcomings, whether the authorities not keeping up to date with terrorist tactics (and the terrorists gladly swapped ideas with each other) or government and the public alike not wanting to admit they had a war on their hands, as Styles bluntly named it.

Bon voyage

His book is a reminder of just how dreadful that ‘war’ was, mainly in Northern Ireland, where at least once ‘military policemen used shovels to pick up the remnants of dead soldiers and put them in plastic bags’. Phoned warnings, even hoaxes, could cause anxiety. Styles told of a ransom demand threatening to detonate bombs on the liner QE2. A bomb disposal man parachuted from an RAF Hercules to search the vessel. Until the owners Cunard (who paid the ransom) were happy with their internal security, they arranged for an Army bomb disposal man to sail on each voyage; Styles had to draw up a roster.

Note; the winner of the 2017 Airey Neave Memorial Book Prize will be announced on November 22, and will be presented by Lord Evans of Weardale KCB DL (Jonathan Evans, former Director-General of the British Security Service).

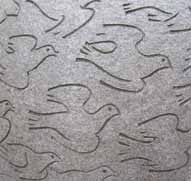

Picture by Mark Rowe; detail from memorial to victims of the 2002 bombings in Bali, central London.