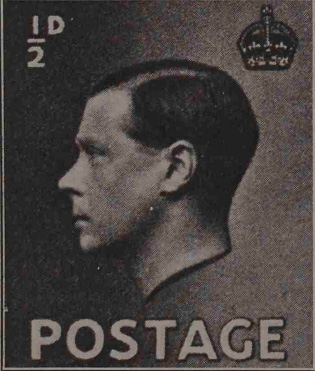

One of the stories of the 20th century was the abdication of the new, bachelor King Edward VIII so that he could marry a divorced American, Wallis Simpson. As with any royals and other VIPs, those people in the public eye needed protection, and got it, even when Edward became the plain (?) Duke of Windsor, as a file at the National Archives in London shows.

It’s happened for as long as there have been bodyguards, heads of state and others needing such guarding, and the others in the entourage who try to tell the bodyguards how to do their job, or not to do it at all.

A typed report from December 1936 suggests some tension: between Insp Evans of the Met Police, with a fellow officer, in Cannes as bodyguards for Edward and Mrs Simpson, and the principals or other of the former king’s friends or courtiers. One of them, Lord Brownlow, sent the Met Police Commissioner Sir Philip Game a telegram claiming ‘total misunderstanding’ and asked Scotland Yard not to withdraw the two officers, who were ‘working very well’.

Evans and the other bodyguard were told to stay where they were. Possibly a dispute had arisen over who was in command of them, because Brownlow apparently had told Evans to ‘pack his bags’; but Evans was told by Scotland Yard ‘that he was to carry out the wishes of Lord Brownlow and Mrs Simpson as far as possible, but that he remained under the orders of the commissioner’.

In a handwritten letter of November 28, 1936 Sir John Simon as Home Secretary asked Sir Philip Game for a report on ‘any special arrangement for watching by the police’ of Mrs Simpson’s house in Cumberland Terrace. The date is significant because this was the height of the political crisis over Mrs Simpson. A pencilled sketch of a reply said the king – Edward VIII was still king, but on the brink of abdicating – had instructed his senior detective to arrange with local police – telling as few people as possible – for advice on making the 16 Cumberland Terrace, the home of Mrs Simpson, ‘burglar-proof’, and ‘to take steps to prevent Mrs Simpson being annoyed by photographers, pressmen and other curious persons’. Because a police beat was in that area when crime was high, the guard on Mrs Simpson was not ‘really abnormal’. The press were a ‘nuisance’, rather than doing any crime, and ‘have of course to be handled tactfully but so far no trouble has arisen’.

From other paperwork, it appeared that the press – above all American newspapers, less able to be cajoled into laying off the story than the British press – were trying to get photos of Mrs Simpson at her home by cameras set up in the back of cars. Police were turning photographers away, claiming that Cumberland Terrace was in the Royal Parks – it is indeed on the east side of Regent’s Park – and photos were not permitted. Police went to an American press agency’s office in the news of the World building, looking to get to the bottom of a Chicago press story about Mrs Simpson. On December 1, police talked with HL Percy, an American journalist who evidently had dug into the Mrs Simpson story in detail. For example he knew the names of the police bodyguards of Edward and Mrs Simpson, as newspapers in America were so keen to feature the story of Mrs Simpson (‘I personally am almost fed up with it’, Percy admitted).

On the eve of abdication, Mrs Simpson was in fact in France, with two Met Police bodyguards. The villa was also guarded by French detectives. To return to the falling-off with Lord Brownlow.

Evans’ side of the story was that he returned to the house after patrolling the grounds and went to see Brownlow, ‘and was standing with my hat in my right hand and my left hand in my pocket’. This was evidently bad manners, because Brownlow told Evans to take his hand out of his pocket and asked ‘where have you been?’ Presumably this was the last straw because Evans asked why Brownlow wanted to know, and Brownlow said to that: ‘I can’t tolerate it any longer. You must return to London tomorrow.’ Evans was adamant that he was staying, and was backed up by London. Just to complicate the story, two Insp Evanses were on duty at the place, told apart by their initials.

On the eve of Edward VIII’s abdication, Sir John Simon agreed to Mrs Simpson still having two bodyguards, although it was ‘a most exceptional measure’ because Mrs Simpson and Edward would now be private citizens. To avoid public criticism, Simon suggested keeping the arrangement ‘as quiet as possible’. To avoid having to answer questions in Parliament, Simon suggested that Edward pay for the guarding himself.

Story continued; part two of four, click here.

Source: file MEPO10-35, freely downloadable from the National Archives, Kew, west London. Visit https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/.