At midday on Wednesday, September 4, Major John Maude, a regional security liaison officer, and Gloucestershire Police Insp Hancock went into the company boardroom of Rotol. It was a factory at Churchdown between Gloucester and Cheltenham, making propellors for such aircraft as the Spitfire and Hurricane. Its work was as vital as could be in the Battle of Britain summer.

The two men were there to interview Edward D’Alessio, an inspector of components. The day before Maude had met the company MD, Captain Stanmore. The company – as the name suggests, a joint venture between the aircraft makers Rolls-Royce and Bristol – had no complaint about D’Alessio. Maude asked if D’Alessio could do any damage, if he so wanted. The MD agreed that the man could pass faulty components, and might come into factory when closed in the evening with a view to sabotage.

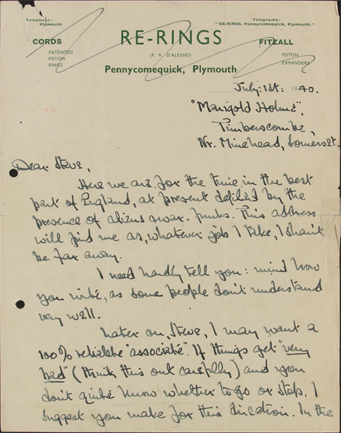

Maude showed D’Alessio a letter. In his report the next day Maude wrote that D’Alessio identified it ‘as being in his handwriting, and I asked him to explain it. It was clear that he was very much taken aback by finding it in our possession’.

A single page letter, both sides of the paper written on – pictured is the front – it was written in early July to a fellow Fascist in Cheltenham. For in the mid-1930s D’Alessio had been the district leader for the leading Fascist party in Britain, The British Union, led by Sir Oswald Mosley, who with hundreds of other members had been arrested after May 23, 1940 as a security risk, once Britain faced a Nazi invasion from across the Channel.

Maude reported: ‘I told him that I thought it must be clear to him that he could hardly be considered a suitable person, in view of his past history and that letter and his present frame of mind, to hold an important position in a vitally important factory’. Maude seconded the local police recommendation for internment.

D’Alessio admitted to Maude that the letter looked suspicious, and in a petition from Liverpool Prison a month later admitted it was ‘ambiguously worded’. To Maude, D’Alessio described himself as a ‘complete pessimist’.

What about the letter looked so suspicious? D’Alessio had only signed the letter with his initials, but his surname was on the headed notepaper, from a former business of his. D’Alessio had asked for a reliable associate: because ‘in the event of certain things happening, I am going to look out for myself, wife and kid first. I have made certain plans and will want some help …. It is not easy to get a reliable ‘body-guard’ and in the event of a showdown, one may be invaluable …. Keep your eyes open. Our chance may be at hand.’

While in detention – he was let out, no longer felt to be a danger to the state, in mid-1942 – D’Alessio variously tried to explain that he was anxious about not having a job; a an anti-Communist he feared a Communist grab for power; or that he had been thinking of getting away by buying a boat and sailing to the Pacific, or the West Indies or west Africa, with others (who would have to pay for the boat as he had no money for one). Born in 1904, D’Alessio had gone through Dartmouth as a cadet and had passed out as a lieutenant engineer in the Royal Navy, but had left in 1927 because (quite apart from the Navy judging him ‘temperamentally unsuitable’) going to sea he felt sea-sick.

It looked as if D’Alessio was being deliberately shifty and hinting at a sinister meaning. For what could a ‘showdown’ be except when the Germans landed, as was expected that summer; and the ‘chance’ could be of Fascists making a grab for power in the confusion.

D’Alessio’s file KV2-2147, downloadable from the National Archives like many other Fascist detainees’, included his long hand-written statement to Plymouth police on June 6, 1940, to ‘remove any suspicion that I am still connected with the BUF [British Union of Fascists] or with any other subversive organisation’. That was prompted by D’Alessio’s dismissal from another inspection job at Camborne in Cornwall. The man disputed that the cause of dismissal was because he was still a Fascist; he maintained (and a letter confirmed) that D’Alessio had resigned from the Fascist movement in February 1940, during a lull in the war, before the emergency of the summer.

Also on file is Rotol’s reply to the Security Service on September 2, 1940, that they had taken on D’Alessio on August 12, as supplied by Ministry of Labour, to work on production inspection, ‘and since inspectors are very difficult to obtain we have decided to keep him on’; although local police had informed the firm he was a one-time BUF man. ‘The police know where he is, if anything occurs they can collect him. Up to date he has given no evidence of any Fascist tendencies, in fact has a tendency to keep himself to himself.’ Plymouth police wrote to MI5 on August 6, 1940 that they heard D’Alessio had started work at Rotol, and file forwarded to police in Gloucester.

On file too from July 29 was a long letter D’Alessio had written to the Admiralty, asking for ‘clearance’ to be able to work, though he had been a Fascist; their reply was that they could not give such clearance.

If the authorities could not take a chance on D’Alessio, why had he been at large all summer and indeed given a job in one of the most sensitive workplaces in the country? Even after Maude’s interview, D’Alessio was allowed to go and live with his wife and baby, at his parents’ home in Somerset, where weeks later he was arrested again and taken to prison and later internment camp with other Fascists on the Isle of Man.

One charitable explanation is that in an era before Spooks-style tech, it took time for letters to pass and for a case to build. Also, the police and Security Service were somewhat snowed under with similar cases – and had Communists and possible enemy agents and the IRA to look out for, quite apart from preparing in case of a German landing. While Mosley and other most prominent Fascists were first rounded up on May 23 – days before the British Army had to evacuate from Dunkirk – a letter from Plymouth’s chief constable – in those days a separate police force – to MI5 of May 16 shows that the Security Service was writing to police forces on Sunday, May 12 to report back on any local Fascists. The German invasion of western Europe had begun on May 10.

Was D’Alessio a threat anyway? He said he wasn’t, that he was loyal; an ‘advisory committee’ that heard appeals did not agree. That panel judged that D’Alessio would probably never have been arrested but for the letter – although that still doesn’t explain the gap of almost two months between the letter falling into the hands of the police and Maude confronting D’Alessio with it.